Across the Bayou, it's Different

- June, 2018 -

Fifteen years ago, the city of New Iberia, LA, disbanded its police department to save money. It didn't go well. This story, which first appeared as seven chronological Instagram posts, is an attempt to document the lives of those most impacted by poor policing.

**Written by Dan Fenster // Images by Bryan Fenster

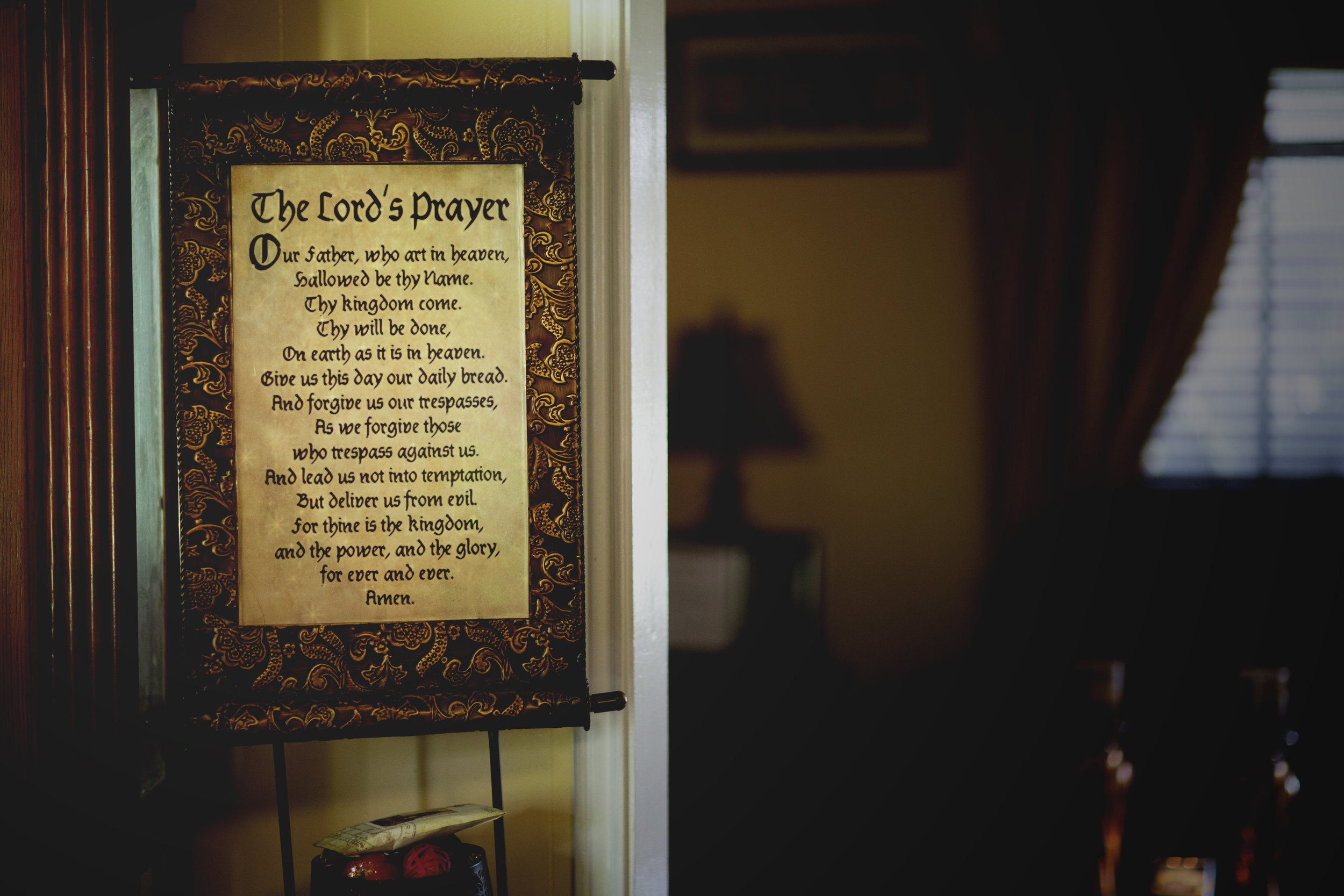

I first met Rosalind Bobb in October 2017, in the sanctuary of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, a cavernous Catholic Church in New Iberia, LA. We were introduced by the Evangelist Donovan Davis, a one-time drug dealer with a halo of Jheri curl and perpetual aviator shades, a man who’d found God in prison and rededicated his life to uniting the survivors of this small southern town’s rising number of homicide victims in prayer. This is much of Rosalind’s work, too. In New Iberia, in October 2017, it seemed, no power short of His might make this plague abate. We were seated—Donovan and I—in the pews, pulpit left, as hundreds streamed in. “This is Ms. Rosalind. She’s a powerful voice in the community,” he said. / “Hi, I’m Rosalind Bobb. My son was murdered in 2006,” she said, matter-of-factly, as if commenting on the weather. I startled at her calm; Donovan hadn’t mentioned she’d be one of the night’s featured speakers. We were gathered for a candlelight vigil following yet another fatal shooting. / “This is a very important evening for all of us,” the pastor began. “We’re banding together and putting our differences aside for a common purpose,” he said, speaking, perhaps, of the congregants differing faiths—held in a Catholic church in deeply Catholic New Iberia, the vigil was billed as interfaith and interdenominational, organized by the preachers and pastors of several differently denominated churches—but there were other obvious differences. Freddie DeCourt, the energetic and overwhelmingly popular, new-ish mayor—with a razor-shave-bald head and jeans-and-blazer wardrobe—cut straight to it: “We as a community have been so divided over stupid things, over railroad tracks or the color of our skin,” he said. “We can’t run from our past but we can learn from it.” “Amen!” Donovan shouted / In 2004, in a shock of penny-pinching, the city abolished its police department. Within a few years, local media was noting a spike in homicides. DeCourt had spent 2017 campaigning for a sales tax to re-fund a police, which had just passed. Donovan leaned into my shoulder: “This tax is the first step. This an unprecedented, landmark moment in New Iberia history,” he said. Then Rosalind ascended the stage.

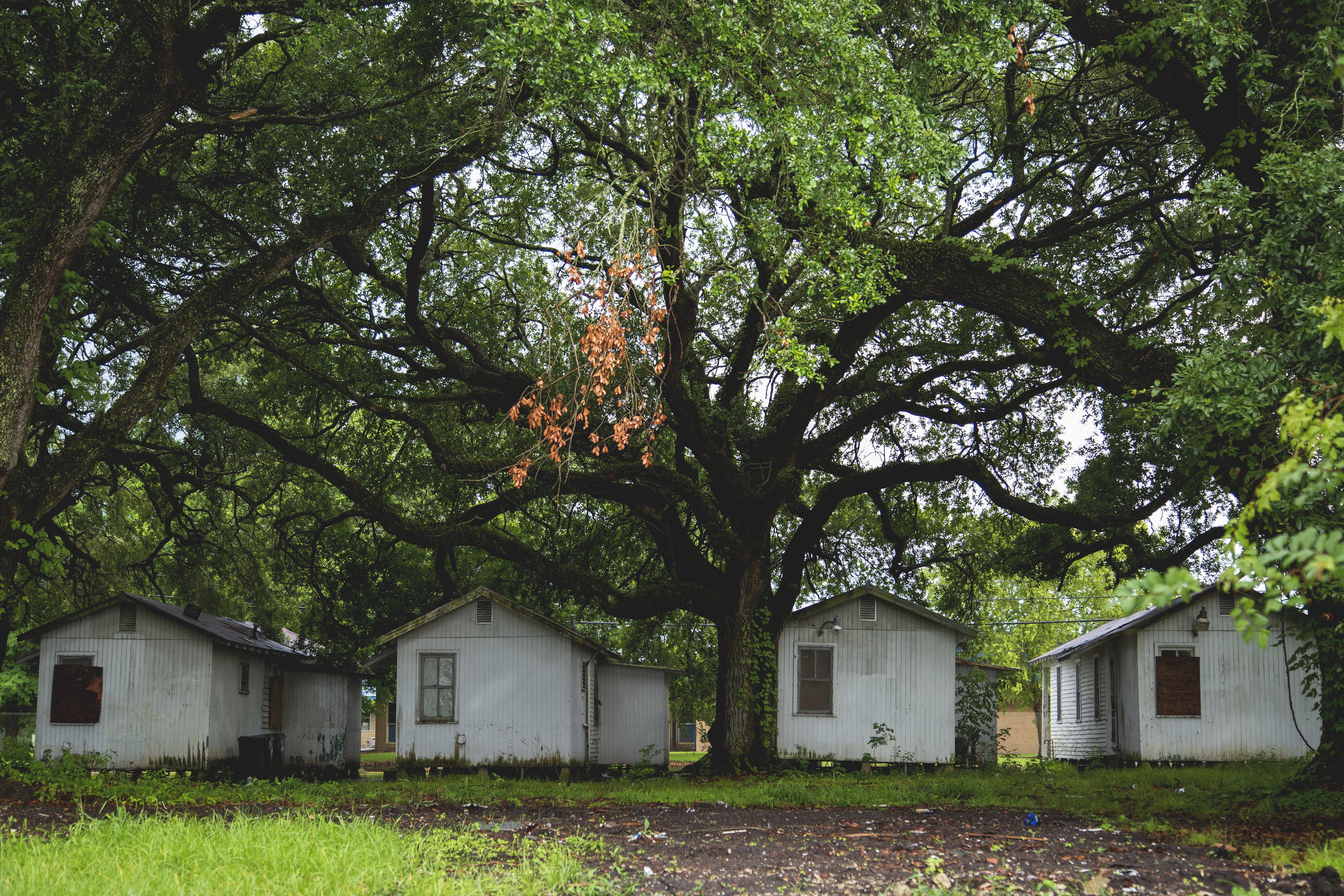

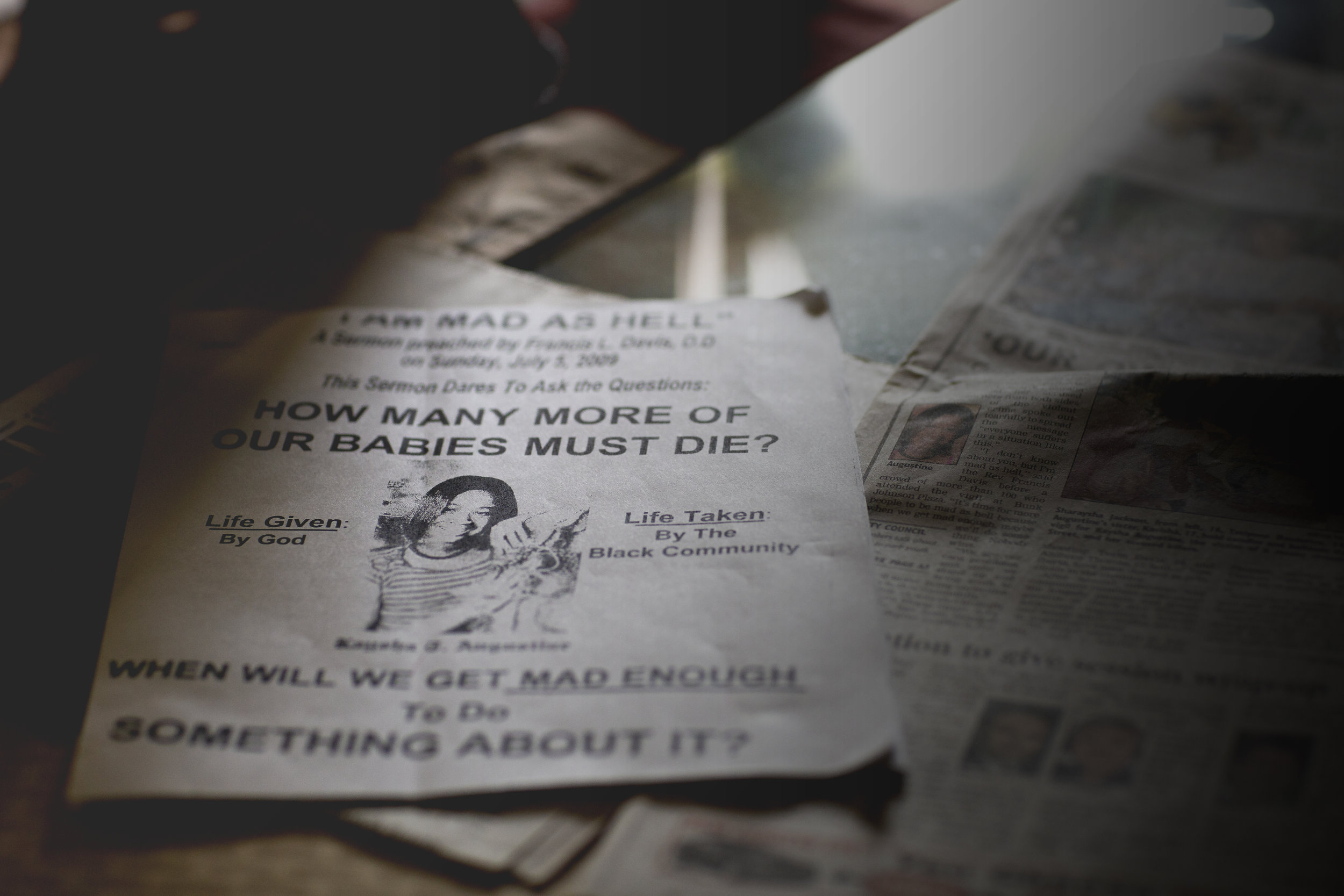

Hopkins runs south from the tracks that cleave this town in two, through the heart of the once-thriving Black business district. Now there are leafy green fields and low-slung auto shops repurposed as storefront churches, anti-violence billboards and “THOU SHALL NOT KILL” signs. Past New Jerusalem Ministry is Field Street, lined with weather-beaten homes and rust-reddened tin roofs, then narrow shotgun shacks raised off the earth, ready for the flood. The Mount Olive Baptist Church #2 is on the left, and the Ref’s Get N’ Go. Then the yards grow lusher and greener, the homes ghostlier, and then you’re in West End Park: rolling green fields of moss-strewn oaks, dappled sun, basketball courts, playground. Along the east wall of the Martin Luther King Recreation Center, built in the boxy fashion of a post-war schoolhouse, is a small room that, for the last three years, Ros has hosted a growing number of grieving parents in every second Thursday of the month. / “Sleepy little New Iberia, known for its oak-shaded Main Street, historic downtown, and as home of Tabasco sauce, is developing a reputation no city wants,” the Independent, a nearby weekly, wrote in 2008. “A rising crime wave that has resulted in five homicides this year as well as numerous home invasions and commercial break-ins has residents nervous and Mayor Hilda Curry angry.” / Ros comes early to set the meetings up with a horseshoe of three tables and a spread of food across a fourth. When I first came, in November of 2017, a fluorescent light hung loose from a ceiling panel, sometimes swaying. People trickle in, kibbitzing, just after 5:00p.m. “You heard who’s in the hospital,” I once heard someone ask; “we’re gonna have to pray for her today.” “You heard who passed?” another asked, another time; “you know the boy—shot on Hopkins, survived, then that cancer got him.” By half past Ros calls all to rise, clasp hands, bow heads, and pray. / In the wake of her own son’s death, in the years of New Iberia’s stark rise in homicides, Ros has become a sort of unofficial grief counselor for the West End. People just find her. “God just took me there,” is how Althea Hill Augustine explained it to me. “It was about one in the morning, and God just took me there.”

On Anderson there were flashing lights and crime scene tape and the police weren’t talking. Someone recognized her as Kaysha's mom and told her to follow the ambulance. Even at the hospital she didn’t know. Through the sliding glass doors, the lobby, the coroner’s office—then she saw Kaysha’s father: slumped over, head bowed, and when he looked up, in his eyes, “that’s really the first time I knew,” Althea said. / Kaysha turned 13 that summer, 2009. She was coming back from Walmart with a cousin. A stray bullet tore across Anderson Street. Althea was just settling into bed when her phone rang. Two nights later she found herself—she can’t quite say why—knocking on Ros’ door at 1am. / “She lays the blame squarely on the sheriff’s department, which is the sole law enforcement agency for the Iberia Parish city of 32,000,” the Independent wrote, before quoting then-mayor Curry: “It took time for it to get this bad,” she said. But fissures had appeared in 2006, when police shot tear gas into a ‘Brown Sugar Fest’ crowd on Hopkins Street, which runs concurrent to the annual Sugarcane Festival on Main Street. “It was only a matter of minutes before someone in the crowd would fire a weapon,” Sheriff Sid Hebert said by way of explanation, then apologized, then pledged to improve the department’s relationship with ‘the community,’ then declined to run for reelection. His successor, Louis Ackal, won by pledging to reduce crime and improve ‘community relations.’ “I am confident the new sheriff will turn things around,” Curry told the Independent. By 2016 Ackal was on trial for federal deprivation of rights charges. Deputies testified to the wanton beating of Black men, several fatally, held in pre-trial custody or just out on the streets. “N— knocking,” they called it. In a state courthouse that fall, a dozen deputies pleaded guilty and were sentenced to a variety of prison terms, and Ackal, a former state trooper, was acquitted on all charges and returned to work, where he remains sheriff. / That same year, 2016, Althea’s phone rang again, summoned to Hopkins Street this time, where a spray of bullets had splintered her 86-year-old mother, Bertha’s, front door and, behind it, Bertha’s body.

According to FBI data, in the decade prior to the dissolution of the New Iberia Police Department, in 2004, city police cleared slightly more than 85 percent of all homicides; in the decade since, from 2005 to 2016, the IPSO cleared less than 20. I found these stats late in the year I spent in New Iberia, on the Murder Accountability Project website, which aggregates nationwide FBI homicide data. There, users can split numbers by time or region. Rates have been declining in America since peaking above 90 percent in the 60s, to around 60 percent today. But the MAP tool also showed zero murders in 2015, and Terry Delahoussaye was murdered on Hopkins in 2015. Perplexed, I called Thomas Hargrove, MAP’s founder—a retired reporter and data junkie—and caught him on his daily six-mile walk. He took my call anyway. CDC data is based on the compulsorily reported death records of each state’s vital registrars, he explained, and police data is voluntarily reported by each department. “Let’s see if I can remember how this goes,” he said, conjuring the CDC website in his mind and then guiding me through it, naming verbatim every link, tab, and dropdown menu without prompting. For the last two decades, it appears, parish police have reported barely a quarter of all homicides the CDC has. I read this to him and could almost hear him stopping mid-stride, thought I heard his mouth opening into the middle of a semi-silent WOW. Then he said it, “Wow,” then paused. “That is God awful. That is like the worst reporting I’ve ever heard,” he said. “That is ferociously bad.” / Since 2008, when Ackal took over, the IPSO has all but stopped reporting homicide data to the FBI. I asked IPSO Public Information Office Wendell Raborn for data from the missing years, but he had little. “These are not stats that we keep,” Raborn said.

Terry Delahoussaye had just left his siblings at the Seafood Connection on December 4, 2015, where they celebrated his 62nd birthday, off to see a cousin who’d recently lost a son. He was to cook for the memorial service, as he was often called to do. He left with gold jewelry on and some money in his pocket, and his body was found relieved of these goods on Hopkins the next morning. / “The only thing we’ve vowed is to never let his case become a cold case,” his sister, Dorothea, told me. Four years on, it remains cold. / The first year the parish took over, Deanna Landry’s son, Nelson Jr., left their apartment in the Bacmonila Homes in a brand new car and never returned. Police called two days later to say they’d found the car. “They told us if we wanted we could come take the car. But that’s part of a missing persons report! Don’t you need it for evidence?” she said. “They said they weren’t aware of a missing persons report. They said okay, they’ll take it to forensics.” In February, Nelson Jr.’s body was found outside of town, his head submerged in a crawfish pond. A decade later, it remains unsolved. “I would go to the Sheriff’s office every day and ask to speak (with him). He was never available,” Deanna said. / “The sheriff’s department is not doing their job,” Kevin Bowser, whose brother, Deondrick, was murdered in January—still unsolved—told me this summer. Two nights prior he’d called in shots he’d heard and police told him they only had “three officers on patrol, one in New Iberia” he said. “How you going to respond with that?” / “The only time we’ve felt the sheriff’s presence was when they had IMPACT,” said Cynthia Lewis, referring to the official name of Ackal’s “N— knocking” narcotics squad—“and that was just to beat on us for any old reason.” Her son, Dante, was murdered—unsolved—on Hopkins, March 2017. A video of it went on Facebook. “It’s so hard, because I still don’t know anything,” she said. “The streets know more than you, and they’re talking. Everybody seems to know but me and the police.”

“First of all,” Hargrove stormed, “you haven’t a clue whether murders are being solved in your parish. This is literally a matter of life and death. Illinois is a great case in point.” In 94 that state stopped reporting homicides to the FBI. Hargrove sued for and eventually acquired the missing numbers: the state now leads the nation in murders. “People were cheated! They were not given information on how bad things were and so they were unable to tell their elected representatives: this is unacceptable!” / Jeremy Bentham reasoned centuries ago that the certainty and celerity of apprehension and punishment does more to deter crime than any other factor. “When police start to devolve so that they’re just not solving murders, well, they’re more likely than not to get a higher number of murders,” Hargrove said. Ricky Delahoussaye, Terry’s brother, had a different take. “When it happens across the bayou, it’s different,” he said. “When a white guy gets shot they treat it different.” Deanna Landry agreed. “If you call and say there’s a drug deal going on, they’ll come right away. But if you call and say somebody’s dying at the end of the street, they’ll be here in 40.” / Over-policed yet under-protected. It’s the flipside of Ackal’s brutality. / “Everywhere in Southern Negro communities I have met the complaint from law-abiding Negroes that they are left practically without police protection,” wrote Gunnar Myrdal in 1944. “As long as Negroes are concerned and no whites are disturbed, great leniency will be shown in most cases.” And the Kerner Commission, in 1968: “If a black man kills a black man, the law is generally enforced at its minimum.” And Jill Leovy, in 2015, on surveys conducted in Harlem and Watts: “The strength of ghetto feelings about hostile police conduct may even be exceeded by the conviction that ghetto neighborhoods are not given adequate police protection...Forty years after the civil rights movement, impunity for the murder of black men (remains) America’s great, though mostly invisible, race problem.” Or Ricky Delahoussaye, in 2018: “It feels like they’re just saying, ‘let the n—s kill the n—s.”

On July 1, 2018, city cops began patrolling the streets of New Iberia for the first time in 15 years. On the second Thursday of that month, at 5:13pm, Donovan Davis stood at the corner of Robertson and Corinne, where, two weeks earlier, Toussaint Johnson, 28, was shot and killed. Davis had planned a prayer vigil there three times already, but it was the beginning of hurricane season, and heavy rains and flooding had cancelled each. There was no rain that second Thursday, just the unforgiving sun and the sticky heat of summer. He pulled a white kerchief from his pocket and dabbed at his brow and mouth as a phone call came in. “Praise God, how you doing brother?” he said. New beads of sweat had already gathered at his temple. / Across town, in the West End Park’s MLK Center, a youth basketball game raged, as attendees of Ros’ grief group began trickling into the small room beside the gym. “Look at that, they fixed the light,” someone said. Above, the loose fluorescent bulb had been secured back into place. At 5:36pm, Ros said: “Alright y’all, I think we’re ready,” then began: “You know, the devil tried to shut this down. Almost did, with all this rain. But I said: Not today, devil!” A cheer from the basketball game could be heard from the gym next door. “Can everybody stand up and come over here and join hands in prayer to get this meeting started?” / By six, a KATC News van had parked next to Davis on Corinne to film the vigil. / Downtown, at 6:26pm, city officials, members of the new police department, and news crews all bowed their heads in a packed dining hall on Main Street. Behind a podium, a young man began a prayer. / “We pray for the protection of this city,” he said. Behind him, a painting of an American flag hung, with a boy and his dog in a grass field silhouetted in front of it. “We pray that the police know what’s going on; that, when something happens, they get to the spot in a timely manner,” the boy said. In the painting, the boy angles a rifle toward four birds in flight, ready to fire. “We pray they protect this area,” the boy said, to a round of Amens. Then they all pledged allegiance to the flag behind the boy. / Blocks away, a gaggle of children were playing in the street.

![[ @bryanFenster ]](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5395c28ee4b0534a362b2292/1264466d-4418-4e93-a0bc-801be33061e2/HEY_BROTHER_LOGO_FINAL.png?format=1500w)